Happy Feast Day to St. Martha, who, as we know, kicks dragon butt. :)

author

Happy Feast Day to St. Martha, who, as we know, kicks dragon butt. :)

Yesterday, I wrote about the ADA as it celebrates 25 years, and what it's meant to me, personally, as well as what still needs to be fixed.

Today, I'm going to write about a specific segment of life and the ADA: churches. Specifically, Catholic churches and schools.

The ADA mandated that buildings erected after the law went into effect had to be what we call "handicapped accessible," meaning people who use wheelchairs or crutches or what have you could access them. But, like this piece in the Cleveland Plain Dealer says, it didn't say how that had to happen. And sometimes it could be a little ridiculous.

At my school, for example, there were ramped entrances--but you couldn't access the second floor of the building, where the 3-8 grade classrooms were. The bathrooms weren't handicapped accessible. One of the girls' restrooms on the first floor required going down a short flight of stairs to get to it. This is the sort of thing that made one ponder common sense--didn't the builders of the school ever think someone might be injured and need an elevator to get to class? Or, at the very least, make the first floor of a building all one level? What sense does it make to have to go down three stairs to get to the bathroom?

(This strange phenomenon I've also seen in older public schools. What was this about, architects?)

In the many churches I've been in, only a few have had dedicated spaces for wheelchairs in the sanctuary, and no, open space at the back of the church doesn't count. I've seen one handicapped accessible confessional in my entire life.

Some church restrooms might have grab bars, but how would a person get into the bathroom? There's no button to push, and the maneuverability required to get in is truly amazing. I was a member at a parish where to get to the bathroom, one had to open a door, which led to a very small hallway, then open another door to get to the bathroom. How is a disabled person supposed to do all this that in a space that's probably not wide enough for a stroller?

Doors that separate the vestibule from the sanctuary--are they handicapped accessible? Most likely not. Sure, they might be propped open, but what if they're not? (My church, not to brag, is really good about this. We have handicapped accessible switch plates on the outside doors and inside doors.)

We've all seen churches that hide their handicapped entrances so well that it's like a scavenger hunt for someone to get in. Couldn't we make God's house a tiny bit easier to access? We've already talked about handicapped parking spaces, and these are especially important in a place like church.

I've never been to a church that provides homily notes, and I'd like those a lot. Some churches have telecoil systems installed that can help people with hearing aids, or even CIs like mine, if you have the right equipment or programs on your processor. But homily notes on websites would be nice, as would appropriate speaker systems, so everyone can hear. Use the microphones, guys! Also, bulletins in braille? I've never seen that. Does that even exist? Or hymnals or missals in braille? Never seen those, either. (Assuming there's a demand for it....I mean, I'm guessing there are a few blind Christians? :) )

The worst, though--and I hate to say this--are Catholic schools. Very few of the ones I know provide appropriate help/accommodations for physical or intellectual disabilities. The thought is that if you need those services, you have to go to your public school. What does that mean for parents who want their children to have a Catholic education? Homeschooling, I suppose.

Here are two excerpts from a local, independent Catholic school's handbook (Independent meaning they aren't part of the diocesan school district):

“ [Name of school] does not have the resources to provide evaluation and intervention services. Referrals will be made to the student’s district of residence.

[Name of school] does not have the facilities for students with serious disabilities.

”

So, if you have a child that might be in a wheelchair, or needs additional services--sorry, you can't send your kid here. (And also, who defines "Serious disabilities"? Ten bucks says it's not a medical professional... )

(In a quick look around of my diocese's school district website, I couldn't find anything on accommodations for disabled students. My elementary school did provide intervention services, and I know they've beefed this up since I graduated. So this is an area where strides are being made.)

This isn't something that's just limited to elementary schools. No one will make the argument that there's an overflow of orthodox Catholic colleges. So the fact that one of them, Wyoming Catholic College, can make being physically in shape--and in good shape--part of their admissions program is reprehensible to me.

The following is from their website:

“I am disabled and cannot participate in the Outdoor Leadership Program (OLP). Can I still attend WCC?

A

Unfortunately, the College cannot accept students unable to meet the physical demands of the OLP, which is an integral part of the College’s academic program. An applicant who is denied medical clearance cannot be accepted into WCC.”

This makes me angry. Really angry, actually. WCC has a reputation of being a top-notch, orthodox Catholic college--and I wouldn't have been able to attend. Nor could anyone else who has, say, cerebral palsy, or is blind, or has any other number of physical disabilities. We can't attend because the school has a program that is unaccessible to anyone who wasn't blessed with good health and physical ability.

I realize that they are a private school, and have the right to impose standards for admission, just like all colleges do. But the fact that a Catholic School--which serves a God who accepted everyone, no matter their physical ability--has standards like this, is maddening. Truly, deeply maddening. Maybe if there was an abundance of excellent Catholic colleges, this wouldn't be so bad. But there isn't. And this isn't just a standard like a GPA, or an ACT/SAT/AP test grade for a scholarship. This is a line about basic physical ability.

Public schools can't have standards like this, because they receive federal money, and thus they're prohibited from doing it by the ADA. But when did Catholic schools become places for only the super- intelligent and able-bodied? I realize that funding is an issue. I'm not naive. But shouldn't the message be that however God created you, there is a place in our school--which has Christ as its reason for existence?

I've always loved this saint, and while she's not as obscure as some of the other saints we've talked about this week, her story is definitely worth telling.

Elizabeth was born on August 28, 1774 (she was a contemporary of Jane's!) and was raised Anglican. Her father was a New York City doctor. Her mother died when Elizabeth was three. Her father remarried, but that marriage ended in separation. For a few years, Elizabeth lived with family in New Rochelle while her father studied in London. A gifted horsewoman, she also spoke French and loved music, poetry, and nature.

At the age of 19, she married William Seton, a wealthy businessman who worked in the import trade. They had five children: Anna Maria, William II, Richard, Catherine, and Rebecca. The family was socially prominent and happy, and Elizabeth was heavily involved in charitable activities.

William's business went bankrupt due to the Napoleonic Wars., and he was diagnosed with tuberculosis. Elizabeth, William, and Anna went to Italy for the climate, hoping for a cure, but William died. God, however, had other plans for Elizabeth's time in Italy.

After William's death, she stayed with the Fellici family, who were William's friends. They were devout Catholics who had Daily Mass said in their chapel. Elizabeth began to attend, and was drawn to their faith and worship practices. By the time she left Italy, she knew that she would receive instruction in the faith when she returned home. She was received into the church on March 14, 1805.

This wasn't the simple decision it may seem. Anti-Catholic feelings were high in the new country (New York's Anti-Catholic laws had just been lifted in 1804, but Catholics still weren't allowed to vote in some places, and their churches were routinely destroyed), and Elizabeth's family warned her that they would withdraw all financial support from her if she did this. She converted, however, and was left to raise her five children without her family's financial help.

Let's restate that: five kids. no job. Family has abandoned her.

Was she crazy? Maybe.

Fortunately, God provided. She started an academy for young ladies, and with the help of Bishop Carroll of Baltimore, she started an order of sisters--the Sisters of Charity, which still exist today. With her fledgling order and her children, she moved from New York City to Emmitsburg, Maryland, where she opened her first school and first convent.

The first few years in Emmitsburg were hard. Few students, little money, and no luxuries--all of which were hard for her children, who had been raised in the upper echelons of New York City society.

The Stone House, Elizabeth and her sisters' first school/convent in Emmitsburg, MD.

Her two sons joined the Navy, but her daughters helped their mother in her work; however, Anna and Rebecca both died of tuberculosis. Katherine became the first American to join the Sisters of Mercy.

On July 31, 1809, Elizabeth established a religious community in Emmitsburg dedicated to the care of the children of the poor. This was the first congregation of religious sisters to be founded in the US, and its school was the first free Catholic school in America. Mother Seton (as she was known in religious life) can therefore be called the founder of the American Parochial School system.

Elizabeth died on January 4, 1821, of tuberculosis. By 1830, her order was running schools as far west as St. Louis and New Orleans, and had established a hospital in St. Louis. She was canonized on September 14, 1975, by Pope Paul VI.

Her Feast Day is January 4, and she is the patron saint of seafarers, Catholic schools, and the state of Maryland.

“Can you expect to go to heaven for nothing? Did not our Savior track the whole way to it with His tears and blood? And yet you stop at every little pain.

”

OK, she's not the patron saint of butter. I mean, she should be--if anyone in the Vatican is reading this, we could use a patron saint of butter. She is, however, the patroness of milkmaids, and one story about her tells us about her powers over butter: young Brigid once gave a poor man her mother's entire stock of butter, but the butter was miraculously replaced before Brigid's mother found out (I don't know about you, but I'd definitely notice if all my butter was missing).

St. Brigid is one of the patrons of Ireland, along with St. Patrick and St. Columba, and she an exciting life story. Most of the stories agree that she was born into slavery, because her mother was a slave (her father was a chieftain, and his wife forced him to sell Brigid and her mother after Brigid's birth). As a baby, she refused to be fed by a Druid because he was "unpure"--instead, she suckled from a red and white cow. From a young age, she showed special care for the poor , as seen in the butter story, and many miracles are attributed to her, even during her life.

She became a nun and founded a monastery at Kildare in 480. She also founded a school of art and a scriptorium.

Her feast day is February 1 and besides being a patron of Ireland, she is also the patron of poultry farmers, babies, blacksmith, dairy maids, dairy workers, fugitives, and midwives.

“Good evening,” said the Faun. “Excuse me—I don’t want to be inquisitive, —but should I be right in thinking that you are a Daughter of Eve?”

”My name’s Lucy,” she said, not quite understanding him. ”

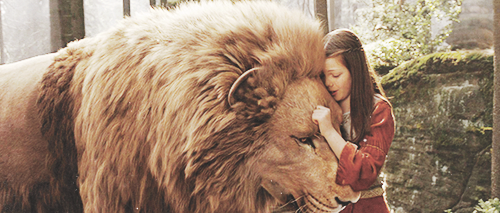

Lucy Pevensie has always been one of my favorite literary characters. I liked her better than the uptight Susan, and definitely better than Mary Ingalls. Lucy, to me, was right up there with Half-Pint and Anne Shirley.

I'd always thought Lucy was, like Anne, fictional. I was very pleasantly surprised when I realized that not only was Lucy real, but that C.S. Lewis had been inspired by the life of Bl. Lucy of Narni, a Lay Dominican from 15th Century Italy.

(Three guesses on where he got "Narnia".....)

Lucy Brocadelli was born on December 13, 1476, in Narni, in the region of Umbria. She was one of 11 children born to Bartolomeo and Gentilina Cassio. She had a vision of the Blessed Mother when she was five, followed a few years later by another vision where Mary was accompanied by St. Dominic. She was inspired to become a Dominican nun, but when her father died and she was left in the custody of an uncle, this plan was thwarted, as he tried to get her married as quickly as possible. Eventually, Lucy entered into a virginal marriage with Count Pietro di Alessio of Milan.

Despite her busy social schedule as a countess, Lucy devoted much time to prayer, instructed the servants in Catholicism, and was well-known for her charity to the poor. Her husband allowed these "strange" behaviors, until a servant told him that he had seen Lucy entertaining a handsome young man in her room. When Pietro went to confront his wife, he saw her studying a large crucifix. The servant said the man she'd entertained looked just like the carving of Christ on the cross.

Eventually, though, Pietro's patience ran out, and her locked her in her room for the whole of a Lenten season one year. She managed to escape and became a third order Dominican, which led her husband to burn down the convent where she'd received the Dominican habit.

In 1495, Lucy joined a community of lay Dominicans. She received the stigmata and was frequently found in spiritual ecstasy. Her fame spread so that a stream of visitors came to see her and receive council. Pietro pleaded several times for her to return as his wife, but finally he gave up. He eventually became a a Franciscan friar and notable preacher.

She founded several convents and served as prioress. She died in 1544, after struggles within her Dominican community and severe restrictions placed on her by the convent's prioress. When she died, so many people came to pay respects and see her body that the funeral had to be delayed for three days.

The connection between Lucy of Narni and Lucy Pevensie, according to Walter Hooper, is that Blessed Lucy could see things that other people couldn't--like her visions--which Lewis incorporated into the story (In Prince Caspian, for example, Lucy is the only one to see Aslan for most of the story):

“After years of study it seems to me that Lewis’s character, Lucy, bears such a very strong resemblance to your saint – the inner light of Faith, the extraordinary perseverance – I don’t think the naming of his finest character Lucy can be other than intentional. I think Blessed Lucy of Narnia has furnished the world with one of the most loved, and spiritually mature characters in English fiction. And if I’m wrong? Well, let me put it this way. My guess is that when we get to Heaven we will be met by C.S.Lewis in the company of Blessed Lucy of Narnia. What will they say to us? Will they reveal whether Lewis based his Lucy on your saint? I think Blessed Lucy of Narnia and C.S.Lewis will laugh. Then Blessed Lucy will say, ‘We will tell you about that later. Other more important things come first. Jack Lewis and I are here to conduct you into the presence of our Host. After that we can talk about all the things on your mind. But not just yet.’”

(Lucy is also possibly inspired by Lewis' goddaughter, Lucy.)

It probably won't surprise you to learn that, when it came time for me to pick a saint as my patron in the Dominican order, that I chose Bl. Lucy.

A continuation of my Female Saints series

Did you know St. Martha fought dragons?

Seriously, guys. She did a lot more than just make dinner for Jesus. (Not that making dinner for Jesus is nothing, right?)

But most of the time being called a "Martha" is a bad thing, and that's always bugged me a little. We tend to just remember her first appearance in the gospels:

Vermeer, Christ in the House of Martha and Mary

“As they continued their journey he entered a village where a woman whose name was Martha welcomed him. She had a sister named Mary [who] sat beside the Lord at his feet listening to him speak. Martha, burdened with much serving, came to him and said, “Lord, do you not care that my sister has left me by myself to do the serving? Tell her to help me.” The Lord said to her in reply, “Martha, Martha, you are anxious and worried about many things. There is need of only one thing. Mary has chosen the better part and it will not be taken from her.””

If this was all we knew about Martha, then she wouldn't come off too well, would she? But we can also relate to her. Who hasn't had work to do at a party, worried about dishes and serving and the turkey in the oven, while other people are just sitting around, not thinking about everything that needs to be done? It might not be a good reaction, but it's one that we can relate to.

Often, this passage is used to illustrate the "active" and "contemplative" ways of life. There's some merit in that. Mary is the contemplative, at the feet of Jesus, lost in prayer, and Martha is the one who serves Jesus, who works in the kitchen and makes the house ready for His visit. Both sides are important in the Christian life, and to have just one side isn't good.

But Martha is a lot more than just the housekeeper. In the Gospel of John, we see her great faith after her brother, Lazarus, has died:

“ And many of the Jews had come to Martha and Mary to comfort them about their brother. When Martha heard that Jesus was coming, she went to meet him; but Mary sat at home. Martha said to Jesus, “Lord, if you had been here, my brother would not have died. [But] even now I know that whatever you ask of God, God will give you.” Jesus said to her, “Your brother will rise.” Martha said to him, “I know he will rise, in the resurrection on the last day.” Jesus told her, “I am the resurrection and the life; whoever believes in me, even if he dies, will live, and everyone who lives and believes in me will never die. Do you believe this?” She said to him, “Yes, Lord. I have come to believe that you are the Messiah, the Son of God, the one who is coming into the world.””

Martha shows her belief in Jesus here, and testifies, like Peter, that he is the Messiah. She knows who He is. She knows He could have healed her brother if he had been there earlier, but she also accepts Lazarus' death. Her faith in Jesus isn't shaken by this event.

Martha is strong in both her temperament and her faith. She isn't perfect--Jesus tells her that she has to learn the 'better part' in Luke’s Gospel--but she has many admirable qualities that can be overlooked. She has common sense, strength, a desire to serve and take care of her family, and a concern for others.

So--what about the dragons? (Come on, Emily, get to the good stuff.)

Well, that's from a French legend:

“...further legend relates that Martha then went to Tarascon, France, where a monster, the Tarasque, was a constant threat to the population. The Golden Legend describes it as a beast from Galicia; a great dragon, half beast and half fish, greater than an ox, longer than an horse, having teeth sharp as a sword, and horned on either side, head like a lion, tail like a serpent, that dwelt in a certain wood between Arles and Avignon. Holding a cross in her hand, Martha sprinkled the beast with holy water. Placing her sash around its neck, she led the tamed dragon through the village.

There Martha lived, daily occupied in prayers and in fastings. Martha eventually died in Tarascon, where she was buried. Her tomb is located in the crypt of the local Collegiate Church.”

There might not be a lot of dragons around today, but St. Martha is still a good saint to keep in mind when the dragons of chaos and doubt roar in our daily lives.

She's the patron saint of cooks, and her feast day is July 29.

Some people have riveting stories about how they found their confirmation saint. It was a sign from God, a message from above, a huge thunderclap of recognition.

Mine was....sort of random.

When I started my eighth grade year, I knew I'd be confirmed at the end of it. So I started reading books about the saints, in the hope that I'd find one I liked enough to be my confirmation saint. In the Catholic church, you pick a confirmation name--the name of a saint you admire and want to imitate. This saint becomes one of your patron saints, along with any saints you might be named after, or have particular attachment to. (For example, there is a saint Emily--although I'm not named after her--and my middle name is a derivative of Michael, so St. Michael the archangel has always been one of my patrons.) You're not "supposed" to choose a saint you're named after, though--at least you weren't at my school. You were supposed to pick a different saint.

Some people pick saints based on their patronages; in my family, a lot of people chose St. Cecilia, because she's the patron saint of music. (St. Gregory the Great is the patron saint of singers.) St. Christopher is the patron of athletes. My mom had chosen St. Bernadette, and my dad St. Francis of Assisi (although not because he was a big nature/animal fan.) I didn't feel particularly drawn to St. Cecilia (Not that she's not cool!). I was also supposed to choose a girl. If I was a boy, I would've chosen St. John the Evangelist.

So I didn't have any hard and fast winners. I started reading saint biographies that I picked up here and there. (When in doubt, go to books, that's what I say.)

Eventually, I stumbled on a biography of St. Therese that was written for kids. (I didn't know then about the incredibly large amount of books written about her and her family. If I'd picked a saint based on how many books I could read about them, she would've won pretty quickly.) Her life seemed sort of like mine. She grew up with her parents and her sisters. She played with her cousins. She liked going to church. She didn't have visions or die a virgin martyr. She was relatable. And she hadn't died all that long ago, which I thought was sort of interesting. I had thought that saints lived ages ago. The book also mentioned that she entered Carmel on my birthday.

So I finished the book and that was that. St. Therese was my confirmation saint.

As I grew up, I began to realize how intensely popular she was. I learned about the 'Little Way', and read more books about her. I didn't read Story of a Soul until after college, though. When I was diagnosed with a type of TB in high school, I remembered that St. Therese had died of it, and hoped not to imitate her that way. She might have died young (she was 24), but I was only 16!

I liked the Little Way a lot. A lot of people probably say that, but Therese and I grew up in similar circumstances. We were both middle class girls and neither of us was Joan of Arc. I wasn't going to join the army or become a missionary. I didn't think I was capable of great deeds (like Merry in Return of the King).

The year after my confirmation, St. Therese was declared a Doctor of the Church by Pope St. John Paul II. 'The Little Way' was right up there with St. Thomas Aquinas! I didn't fully grasp the implications of that at the time, but I liked how many people were drawn to this French girl who only left her part of France once in her life.

At the time, I didn't realize how powerful St. Therese is. Sometimes she's called Our Lady's First Lieutenant. She's an incredible intercessor for us. But most of all, she's human. Really. She did have ecstatic moments, like St. Teresa of Avila, her predecessor in Carmel. She didn't save France on the field of battle, like St. Joan of Arc, one of her favorite saints. But she realized she didn't have to--that in God's garden, there are all sorts of flowers.

That image, as well as another, resonate powerfully with me. The other is the story of a young Therese:

“At the age of twelve, Therese’s sister Leonie felt she had no further use for her doll dressmaking kit, and stuffed a basket full of materials for making new dresses. Leonie then offered it to her six year old sister, Celine, and her two year old sister, Therese. “Choose what you wish, little sisters,” invited Leonie. Celine took a little ball of wool that pleased her. Therese simply said, “I choose all.” She accepted the basket and all its goods without ceremony. This incident revealed Therese’s attitude toward life. She never did anything by halves; for her it was always all or nothing.

”

I'm a lot like that. I want to choose everything and have everything. St. Therese wrote in A Story of A Soul that she "could not be a saint by halves." And that, more than anything else from her, has been instrumental in my life. She refused God nothing; she took whatever He gave her, and she did it willingly. That might not have mean she liked it. But she did it.

(Mother Teresa, who chose St. Therese as her name in religious--although spelled differently--had much the same attitude, saying she took from God whatever He gave her.)

So while my 13 year old self didn't think too hard about her confirmation saint, twenty years later, I'm pretty glad she didn't, because she might have missed the treasure that is St. Therese.

This post is part of a weeklong series on Women Saints.

Earlier this week, I read this article in the Washington Post about Josh Duggar's inappropriate (and quite frankly, gross) actions against several of his sisters and another family friend. That alone isn't worth blogging about, though. What is worth writing about are are similarities and difference between sin and crime--something that the author of this piece doesn't seem to understand. The author seems to think that "repentance" is equal to getting off scot-free, and that there isn't any sort of price to be paid for committing sin, whereas with a crime, there is a cost--jail, usually, or a fine of some sort.

Earlier this week, I read this article in the Washington Post about Josh Duggar's inappropriate (and quite frankly, gross) actions against several of his sisters and another family friend. That alone isn't worth blogging about, though. What is worth writing about are are similarities and difference between sin and crime--something that the author of this piece doesn't seem to understand. The author seems to think that "repentance" is equal to getting off scot-free, and that there isn't any sort of price to be paid for committing sin, whereas with a crime, there is a cost--jail, usually, or a fine of some sort.

When you treat this as a sin instead of a crime, you let everyone down...The behavior alleged was a crime, not a sin.

Actually, it's both. If I commit murder, I have sinned and committed a crime. Same with theft, abuse, using illegal drugs, etc. There are some things that are sins but aren't crimes, like adultery. You can't go to jail for sleeping with your co-worker's wife. No one's going to lock me up for not observing the sabbath or for taking God's name in vain (at least in the United States).

Let's look at a few terms, here, because the author didn't, and that's a big problem.

First off, what is sin? Here's how the Catechism defines it:

1849 Sin is an offense against reason, truth, and right conscience; it is failure in genuine love for God and neighbor caused by a perverse attachment to certain goods. It wounds the nature of man and injures human solidarity. It has been defined as "an utterance, a deed, or a desire contrary to the eternal law."121

1850 Sin is an offense against God: "Against you, you alone, have I sinned, and done that which is evil in your sight."122 Sin sets itself against God's love for us and turns our hearts away from it. Like the first sin, it is disobedience, a revolt against God through the will to become "like gods,"123 knowing and determining good and evil. Sin is thus "love of oneself even to contempt of God."124 In this proud self- exaltation, sin is diametrically opposed to the obedience of Jesus, which achieves our salvation

There are also different types of sin.

We see, in this definition of sin, that no sin only hurts one person. Sin is an offense against God. It is opposed to grace. Sin removes grace from your soul, and places you farther from God.

Now, what is crime? According to Merriam-Webster, crime is:

: an illegal act for which someone can be punished by the government

: activity that is against the law : illegal acts in general

: an act that is foolish or wrong

So both sin and crime are about doing things that are wrong, whether by God's law, the law of the state/country/county, or by Natural Moral Law. Essentially, Natural Moral Law states that even if you never met a Christian, read the Bible, or ever heard of Jesus Christ, there are some things that humans know are intuitively wrong. As Catholicism for Dummies puts it:

Moral law is natural because it’s known by reason — not written in stone or on paper, like the Commandments or the Bible. It’s moral because it applies only to moral acts — actions of human beings that involve a free act of the will. (It doesn’t apply to animals, because they don’t have the use of reason.)

What Josh Duggar did (and he confessed to doing it, so this isn't alleged behavior) is both a sin and a crime. He committed a sin by violating one of God's commandments--sexual acts outside of marriage are wrong. (While the Duggars have some pretty extreme courtship measures, the general message of "no sexual activity until you're married" is a tenant of Catholicism, as well. But full-frontal hugs are allowed, and I never dated with my siblings as a chaperone, etc. The Duggars embrace a pretty hard-core version of purity, which the article discusses.) So that's sin. However, it's also illegal to perform sexual activities on others without their consent, so that's the crime portion of the situation. Both require confession and punishment/penance, but they go about it differently.

If the Duggars were Catholic, they would have strongly suggested that Josh confess this sin (you can't compel a confession. The penitent has to come to it of his own free will and with a proper spirit of contrition), and he would have received a penance. After the penance was completed, Josh would have been fully absolved from the sin, thus returning to a state of grace and a state of friendship with God. The Catechism says (my emphases)

1468 "The whole power of the sacrament of Penance consists in restoring us to God's grace and joining us with him in an intimate friendship."73 Reconciliation with God is thus the purpose and effect of this sacrament. For those who receive the sacrament of Penance with contrite heart and religious disposition, reconciliation "is usually followed by peace and serenity of conscience with strong spiritual consolation."74 Indeed the sacrament of Reconciliation with God brings about a true "spiritual resurrection," restoration of the dignity and blessings of the life of the children of God, of which the most precious is friendship with God.75

1469 This sacrament reconciles us with the Church. Sin damages or even breaks fraternal communion. The sacrament of Penance repairs or restores it. In this sense it does not simply heal the one restored to ecclesial communion, but has also a revitalizing effect on the life of the Church which suffered from the sin of one of her members.76 Re-established or strengthened in the communion of saints, the sinner is made stronger by the exchange of spiritual goods among all the living members of the Body of Christ, whether still on pilgrimage or already in the heavenly homeland:77

It must be recalled that . . . this reconciliation with God leads, as it were, to other reconciliations, which repair the other breaches caused by sin. The forgiven penitent is reconciled with himself in his inmost being, where he regains his innermost truth. He is reconciled with his brethren whom he has in some way offended and wounded. He is reconciled with the Church. He is reconciled with all creation.78

(The entire section on confession is worth a read, if you're interested, or this post)

So, not only would Josh's sins have been forgiven after confession, but he also would've received grace to strengthen him against committing sin again. (as I tell my first graders--GRACE IS AWESOME.)

Now, that being said--confession heals the person's relationship with God. When criminal activity occurs, the Church believes that the process of law and due process has to happen for the common good of society. For example, if a murderer comes and confesses his sin, the priest will strongly urge that person to confess to the authorities, as well. It's part and parcel of justice, which is a virtue. If you steal, you not only confess it--you have to pay back what you stole.

So, yes, Josh's parents would've had to turn him in to the authorities. What happens after the crime has been admitted is a different thing in different localities, and thus outside the realm of this discussion.

However, the thing to remember is that sin hurts everyone. When you sin, you don't just confess and get off scot free. There has to be penance, there has to be contrition and yes, you have to do your penance. The author of this piece is wrong when she suggests that sin and crime are different things, and that one is more or less serious than the other. Sin and crime are both offenses against other people, and both must be dealt with accordingly, whether sacramentally or judicially.